BBC News World

BBC

BBCEvery morning, Camami rosa wakes up the flame of cardboard scraps on a makeshift stove in his yard.

The boxes he brought home previously held 800,000 high-tech solar panels. Now, they burn his fire.

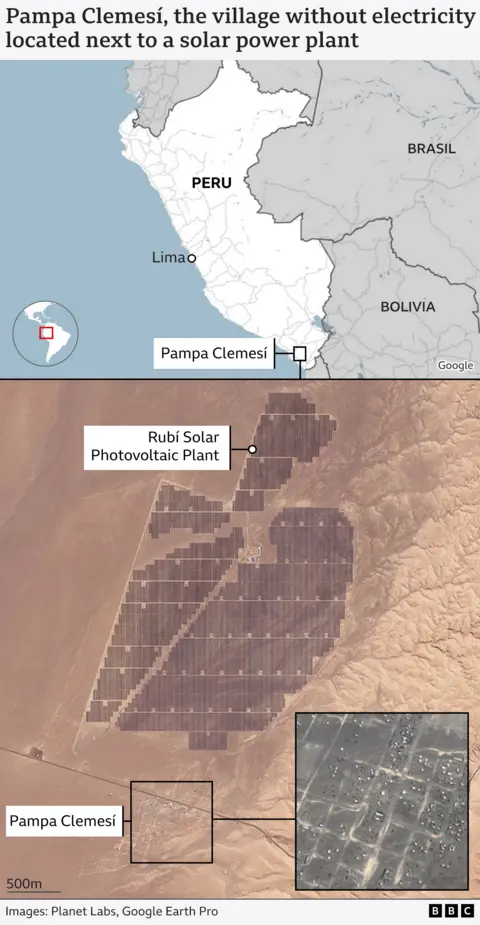

Between 2018 and 2024, the panels were installed in rubí and clemesí, two large solar plants in the Moquaro region of Peru, about 1,000 km southern capital, five. Together, they shape the largest solar solar in the country – and one of the largest in Latin America.

From his house to a small settlement of Pampa Clemesí, Rosa see the rows of panels that shine beneath the white winds. The plant rubí 600 meters away.

However his house – and the rest of his village – remained in full dark, with no grid-fed grid.

Power from the sun, but not at home

None of the Pampa Clemesí’s 150 residents are accessed by the National Power Grid.

Some have solar panels that Rubí’s operator, orygen have donated, but many cannot afford the batteries and the transferers they need to do. In the evening, they used torches – or simply living in the dark.

Paraox Striking: The Rubí Solar Power Power Plant will make 440 GWH a year, enough to support the power to 351,000 homes. Moquageua, where the plant is located, an ideal site for solar energy, receives more than 3,200 hours of sunshine each year, more than most countries.

And that disagreement can be more than one country currently experienced a flexible force of force.

In only 2024, the power generation from changes has grown by 96%. The power of solar and air depends on brass due to its high management – and Peru is the second largest producer in the world.

“In Peru, the system is designed around the profit. There is no effort to connect to many places living,” Carlos Gordillo, an Energy expert in the University of Santa María in Arequipa.

Orygen said it fulfilled its responsibilities.

“We participated in the government project to bring power to Pampa Clemesí and has been built a dedicated line in Peru,” Marco Frage also told Peru the Peru of World.

Fratale added that almost 4,000 meters underground cable was installed to provide a power line for the village. Complete $ 800,000 investment, he said.

But the lights never come.

The final step – Connect to the new line of individual households – is the government’s responsibility. According to the plan, the Ministry of Mines and Energy should set about two kilometers of wiring. Work was started at the beginning of March 2025, but did not start.

BBC News World tried to contact the Ministry of Mines and Energy but did not receive an answer.

A daily struggle for basics

Rosa’s little house has no basics.

Every day, he went around the village, hoping to have someone who could save a small electricity to pay for his phone.

“Cause,” he said, he meant the necessary device to stay with his family near Bolivia border.

One of the few people who can help Rubén Pongo. In his larger house – with patios and many rooms – a group of blemish hens fights for atoftop space between solar panels.

“The company gave the solar panels to most villagers,” he said. “But I have to buy the battery, converted, and wiring myself – and pay for installation.”

Rubén has something to dream only: a fridge. But it just runs up to 10 hours a day, and in the crowded days, never.

He helped build a rubí plant and later working on maintenance, cleaning the panels. Today, he attracts the warehouse and driven by the company’s job, even if the plant is just on the road.

Crossing the Pan-American Highway on the foot is prohibited by Peruvian law.

From his roof, the Rubén points in a cluster of glowing buildings at a distance.

“That’s the substation of the plant,” he said. “It looks like a small city light.”

A long wait

Residents of Pampa Clemesí began early in 2000s. Among them was Peter Chará, now 70. He watched 500,000-panels Rubí plant near his door.

Most villages are built from discarded materials from the plant. Pedro stated even their beds from scrap wood.

There is no water system, no correction, no garbage collection. The village once has 500 residents, but due to poor infrastructure, mostly left – especially during Covid-19 pandemic.

“Sometimes, after waiting for a long time, fighting for water and electricity, you feel like to die. Thus.

Dinner by torchlight

Rosa rushed his aunt’s house, hoping to catch the end of the day. Tonight, he cooks dinner for a small group of neighbors who share food.

In the kitchen, a gas fuel heals a box office. Their only lighting is a sugarly run by solar. The dinner is sweet tea and fried dough.

“We just eat what we can keep at room temperature,” Rosa said.

Without refrigeration, protein-filled foods are hard to store.

The fresh yield requires a 40-minute bus ride to Moquage – if they can afford it.

“But we don’t have money to bring everyday.”

There is no electricity, many in Latin America cooking fuel or kerosene, dangerous respiratory disease.

In Pampa Clemesí, residents use gas if they can – wood if they cannot.

They prayed by praying for food, shelter, and water, then food in silence. 7pm it, their last activity. No phone. No TV.

“Our only light is the little torch,” Rosa said. “They don’t show up so much, but at least we can see the bed.”

“If we have electricity, people will return,” said Peter. “We remain because we have no choice. But in light, we can build a future.”

A soft breeze stirs on desert roads, sand lift. A layer of dust has set lampposts in the main plaza, waiting to install. The air signs that come near – and that soon, there is no light.

For those who do not have solar panels, like Rosa and Peter, the dark to sunrise. So do their hope that government works one day.

As many nights before, they prepared for another night without light.

But why do they still live here?

“Due to the sun,” Rosa replied without a doubt.

“Here, we always have a day.”