BBC Afghan Service, Kabul

BBC

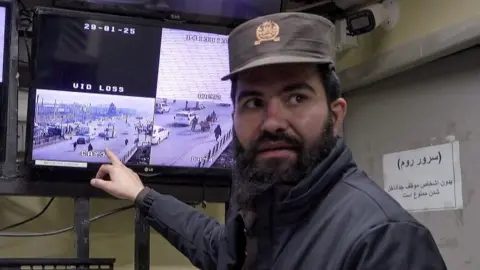

BBCIn a loaded control center, surrounded by many TV screens, the Taliban feast is proud to show the network 90,000 lives of millions of people.

“We tracked the entire city of Kabul from here,” says Khalid Zadran, a spokesman for the chief of the Taliban Police pointing to one of the screens.

The authorities say that such an observance helps fight crime, but critics fear to use in hitting a tight Taliban Under their translation of Sharia law.

BBC is the first international journalists permitted to see the system that works.

Inside the control room, police officers sit in rows watching live streams from thousands of cameras, keeping tabs of six million people living in Kabul.

From car license plates in facial expressions, everything is monitored.

“In some cases, if we noticed groups of people and suspects they could be involved in drug use, criminal activity, or something suspected of local police,” Zadran said.

“They quickly investigate the attitude of gathering.”

Under the previous government, Kabul threatened daily attacked from Taliban and called militant states of Islam, as well as high profile kidnappings and car-jackings. When the Taliban returned to the power of 2021, they promised to crack the crime.

The enthusiastic increase in the number of surveillance cameras in the capital is a sign of growing sophistication in a way of the Taliban enforcing law and order. Before their return, only 850 cameras are in the capital, according to a spokesman for security forces driven out of power.

However, in the last three years, the authorities also introduced various draconian measures limiting women’s rights and freedoms. The government of the Taliban was not formally recognized in any country.

The BBC monitoring system shows Kabul has the option to track people by identifying the face. At the corner of a picture on the screen pop up on each surface categorized by age, gender, and if they have a beard or a face mask.

“With clear days, we can zoom in individuals (s) miles away,” Zadran says, promoting a camera that focuses on a busy traffic traffic.

Taliban also guarded their own staff. In a checkpoint, as soldiers open the trunk of a vehicle for inspection, operators are targeting their lenses, zooming in to scrutinize the contents inside.

The interior ministry says cameras have “significantly contributed to the development of salvation, withdrawal of crime rates, and easily contains offenders”. It increases CCTV identification and motorcycle controls causing a 30% reduction in crime rates between 2023 and 2024 but cannot verify these numbers.

However groups are concerned about who are monitored and how long.

Amnesty International says the installation of cameras “under the ‘National Security’ sets a template for the Taliban to continue the basic rights of people in public spaces”.

Through female men are not allowed to be heard outside their homes, even when practicing it is not strictly implemented. Teenage women are disabled from secondary school access and higher education. Women are prohibited from many forms of work. In December, women trained midwives and nurses told the BBC that they ordered not to return to classes.

While women continue to be seen in streets of cities like Kabul, they should wear a covered face.

Fariba *, a young graduate living with his parents in Kabul, did not find a job since the power of the Taliban power. He told BBC “important concern that surveillance cameras can be used to monitor women’s hijabs (veils)”.

The Taliban says the city police have access to the CCTV system and the launch of virtue and avoiding vice ministry – the police of the Morality.

But Fariba was worried about the cameras more at risk for the opposition of Taliban rule.

“Many individuals, especially members of the ex-military, human rights advocates and protesting women, struggling to move freely and always live in secret,” he said.

“There is an important concern to use surveillance cameras to monitor women’s hijabs,” he said.

Meanwhile, humans of human rights, says Afghanistan has no laws of data protection in place to regulate how CCTV footage is collecting.

Police say that data is hidden for three months, while, according to the interior ministry, the Camer ministry does not threaten the privacy of a specific person in charge “.

Cameras appear to be made of Chinese. The control room monitor and the branding of the feeds seen by the BBC named David, a government-related company. Earlier reports that the Taliban of Talks of Huawei technologies in China to buy cameras denied by the company. Taliban officials refuse to answer the BBC’s questions where they are specifying the equipment.

Some of the installation cost of new network falls into ordinary Afghanaries monitored by the system.

In a Central Kabul house The BBC talks to Shella *, asking to pay for some cameras installed on the streets near his home.

“They asked thousands of Afghanis from every household,” he said. This is a large amount in a country where women with jobs can earn about 5,000 Afghanis ($ 68; £ 54) a month.

The humanitarian condition of Kabul, and in Afghanistan in general, remained more years of fighting. The country’s economy is in the crisis, but international funds of assistance has largely stopped because the Taliban returned to power.

According to the United Nations, 30 million people need help.

“If families refuse to pay (for cameras), they are threatened with water cuts and energy for three days,” Shella added. “We have to take loans to cover costs.

“People are hungry – what are these good cameras?”

Taliban says when people don’t want to contribute, they can put on an official complaint.

“Participation is volunteer, and donations of hundreds, no thousand,” Khalid Zadran, Taliban Police spokesman, insulting.

In spite of the insecurities, the rights campaigns and outside Afghanistan continue to have concerns how a strong surveillance system will be used.

Jaber, a vegetable seller in Kabul, says the cameras represent the other way in which afghans are made to feel powerless.

“We were treated like rubbish, denied the opportunity to live with life, and the authorities consider us useless,” he said to the BBC.

“We can’t do anything.”

*The names of women interviewed for this piece have changed for their safety

With additional reporting Peter Ball