Venture capitalist Modar Alaoui said robots have long been viewed as a poor choice for Silicon Valley investors — too complex, capital-intensive and “frankly boring.”

But business Artificial Intelligence Boom A spark that has been ignited for a long time The vision of building a humanoid robot Robots can move mechanical bodies like humans and do things humans do.

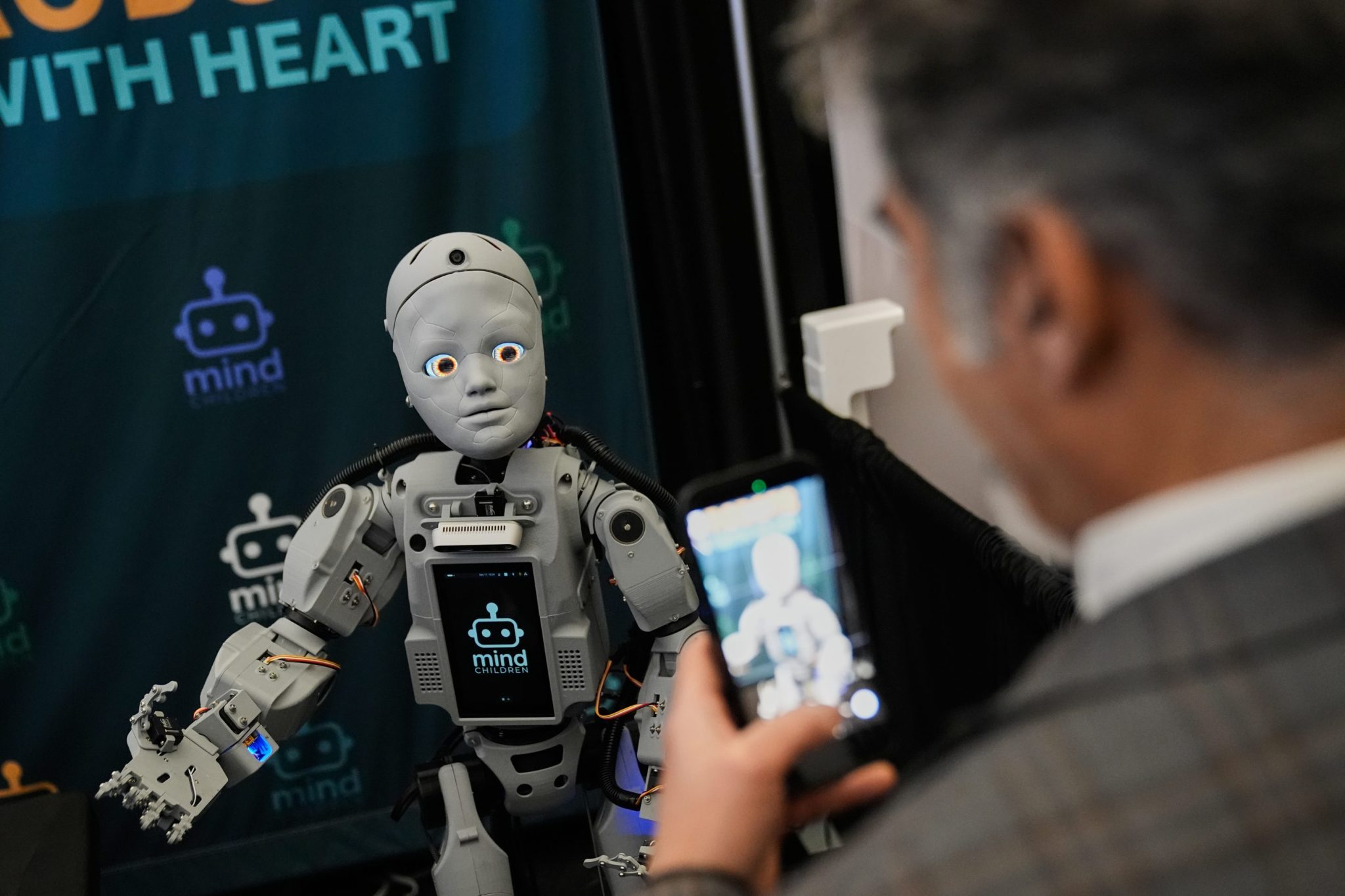

Alaoui, founder of the Humanoid Robotics Summit, brought together more than 2,000 people this week, including top robotics engineers from Disney, Google and dozens of startups, to showcase their technology and discuss how to accelerate the emerging industry.

Alavi said many researchers now believe humanoid robots or some other physical embodiment of artificial intelligence “will become the norm.”

“The question really is how long it will take,” he said.

Disney’s contribution to the field is a walking robot version of the “Frozen” character Olaf that will roam on its own at Disneyland theme parks in Hong Kong and Paris early next year. Recreational, highly complex robots that resemble humans or snowmen are already emerging, but the timetable for “universal” robots that become productive members of the workplace or the home is still far off.

Even at a conference aimed at drumming up enthusiasm for the technology, held at the Computer History Museum, a temple to Silicon Valley’s previous breakthroughs, doubts remained high whether truly humanoid robots would take hold anytime soon.

“There’s a very, very big mountain to climb in humanoid robotics,” said Cosima du Pasquier, founder and CEO of Haptica Robotics, which works to give robots a sense of touch. “There’s still a lot of research that needs to be addressed.”

The Stanford University postdoctoral researcher came to the conference in Mountain View, California, a week after launching her startup.

“The first customers were actually people here,” she said.

According to researchers at consulting firm McKinsey & Company, about 50 companies around the world have raised at least US$100 million to develop humanoid robots, including about 20 in China and 15 in North America.

McKinsey partner Ani Kelkar said China is in the lead in part because of government incentives for parts production and robot adoption, as well as a directive last year to “build a humanoid ecosystem by 2025.” Presentations from Chinese companies dominate the exhibition portion of this week’s summit, which takes place on Thursday and Friday. The most popular humanoid robot at the conference was made by China’s Unitree, in part because researchers in the United States buy relatively cheap models to test their own software.

In the United States, the emergence of generative AI chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini has shaken up the decades-old robotics industry in different ways. Investor excitement has poured money into ambitious startups aiming to build hardware that can give the latest artificial intelligence a physical presence.

But it’s not just crossover hype—the technological advances that make AI chatbots so good at language also play a role in teaching bots how to perform tasks better. Combined with computer vision, robots driven by “visual language” models are trained to understand their surroundings.

One of the most prominent skeptics is robotics pioneer Rodney Brooks, co-founder of Roomba vacuum maker iRobot, who wrote in September that “despite hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars from venture capital and big tech companies donating to pay for training, today’s humanoid robots will not learn to be dexterous.” Brooks was not present, but his paper is often mentioned.

Also missing is a voice for a humanoid robot called Optimus Prime developed by Tesla CEO Elon Musk, a project the billionaire is designing to be “extremely capable” and sell in high numbers. Musk said three years ago that people might be able to buy Optimus Prime “in three to five years.”

Alaoui, the organizer of the conference, is the founder and general partner of ALM Ventures. He previously worked on driver attention systems in the automotive industry and saw similarities between humanoid robots and early self-driving cars.

Near the entrance to the summit, just a few blocks from Google’s headquarters, is a museum exhibit showcasing Google’s 2014 bubble-shaped self-driving car prototype. Eleven years later, robotaxis operated by Google subsidiary Waymo continue to ply nearby streets.

Some robots with human elements are already being tested in the workplace. Oregon-based Agility Robotics announced shortly before the conference that it will bring its portable warehouse robot Digit to a Texas distribution center operated by Latin American e-commerce giant Mercado Libre. Like the Olaf robot, it has inverted legs and is more bird-like than human.

Industrial robots that perform a single task are already common in automotive assembly and other manufacturing industries. They work with a speed and precision that today’s humanoid robots (or humans themselves) would be hard-pressed to match.

The head of a robotics trade group founded in 1974 is now lobbying the U.S. government for a stronger national strategy to promote the development of homegrown robots, whether humanoid or otherwise.

“We have a lot of powerful technology, we have AI expertise in the United States,” Jeff Bernstein, president of the Association for Advancing Automation, said after visiting the expo. “So I think it remains to be seen who is the ultimate leader in this. But right now, China definitely has more momentum in humanoid robots.”