The BBC Korean is Hapcheon

BBC / Hyojung Kim

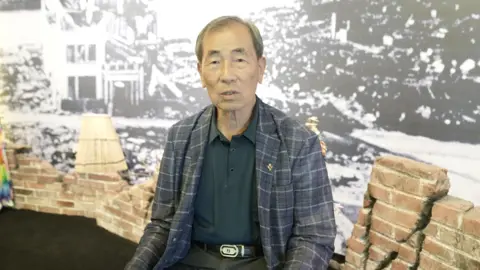

BBC / Hyojung KimAt 8:15 on August 6, 1945, as a nuclear bomb dropped like a stone on the skies in Hiroshima, Lee Jung – before he went to elementary school.

The present-88-year-old waves in his hands seem to try to push memory.

“My father was about to leave work, but suddenly he ran back and told us to evacuate,” he remembered. “They say the streets are filled with the dead – but I am curious about all I remember is crying. I just cry and cry.”

Victim’s bodies “melted only their eyes to see”, said Ms Lee, as an explosion equal to 15,000 tons of TNT consisting of a city of 420,000 people. The rest of the aftercards are also introduced.

“The bomb atom … it’s a terrible weapon.”

It has been 80 years since the above-mentioned ‘little boy’, first atomic bomb, at the center of Hiroshima, immediately killing about 70,000 people. One thousand more will die in the coming months from radiation disease, burning and overflowing.

The destruction made by hiroshima bombings and nagasaki – which carried a decisive end of World War two and Japanese imperials in Asia – Documented in the past eight decades.

The less recognizable is the fact that about 20% of the victims of Korean Koreans.

Korea is a Japanese colony for 35 years when the bomb fell. Approximately 140,000 Koreans live in Hiroshima during the time – many have moved there for compulsory labor, or to survive under colonial exploitation.

Those who survived the bomb of the atom, with their generations, continued to live in a long shadow that day – fighting justice without resolving.

Getty images

Getty images“No one has a responsibility,” Said Shim Jin-Tae, an 83-year-old survivor. “Not the country dropping the bomb. Not the country failed to protect us. America never knows. Korea isn’t really good.”

Mr. Shim now lives in Hapcheon, South Korea: a small county, turned home to many survivors like him and Ms Lee, called “Korea’s Hiroshima”.

For Ms Lee, the shock of that day did not disappear – it came into his own body as illness. He now lives with skin cancer, Parkinson disease, and angina, a condition that comes from poor heart blood flow, which is often revealed as chest pain.

But how much weighs the more the pain doesn’t stop with him. Her son Ho-Chang, supporting him, diagnosed with kidney failure and subjected to dialysis while waiting for a transition.

“I believe that because of radiation exposure, but who can afford it?” Ho-Chang Lee says. “It’s hard to verify scientists – you need a genetic test, being tired and expensive.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHW) speaks BBC gathering genetic data between 2020 and 2024.

The Korean Toll

In 140,000 Koreans in Hiroshima at the time of bombing, many are from Hapcheon.

Surrounded by mountains with a small farm, it is a difficult place to live. The plants were arrested by Japanese occupants, the leaks beat the land, and thousands of people left the country in the war during the war during the war. Others are forced to be conscripted; Some hit the promise “You can eat three meals a day and send your kids to school.”

But in Japan, Koreans are the citizens of the second class – always given the hardest, most pleasant and most dangerous jobs. Mr. Shim said his father was working in a factory with munitions as a compulsory worker, while his mother holds the nails of wooden crismition crates.

After the bomb, this Labor distribution is translated into danger and often fatal work for Koreans in Hiroshima.

BBC / Hyojung Kim

BBC / Hyojung Kim“Korean workers need to clean up the dead,” Mr Shim, who is the director of the branchon of the Hapcheon victims of the Korean bomb, saying BBC Korea. “At first they used the stretchers, but there were many bodies. Finally, they used dust to collect the corpses and the schoolyards burn them.”

“This is most of Koreans doing this. Most post-wars cleaning the war and municipalities are made of us.”

According to a study by Gyeonggi Welfare Foundation, some survivors are forced to clean the waste and convertible bodies. While Japanese evacuees fled to relatives, Koreans without local relationships remain in the city, exposed to radioactive fallout – and have limited medical care access.

A combination of these conditions – bad treatment, dangerous prejudice and structural discrimination – all contributed to an uneven high death of Koreans.

According to Korean Atomic Bauts Bauts Association, the rate of death in Korea is 57.1%, compared to the total rate of about 33.7%.

About 70,000 Koreans were exposed to the bomb. Tolerance, about 40,000 dead.

Outcasts at home

After the bombing, leading to the surrender of Japan and a series of liberty in Korea, about 23,000 Korean survivors returned home. But they are not accepted. Labeled as a disfigure or cursed, they faced prejudice even in their homeland.

“Hapcheon had a leper colony,” Mr. Shim explained. “And because of that image, people think that bomb survivors have skin diseases too.”

Such stigma has made the survivors remain quiet about their condition, he added, suggesting that “safety comes before pride”.

Ms Lee said he saw it “in his own eyes”.

“The wicked men burned or were so poor,” he remembered. “In our village, some people have their withdrawals and faces that are bad wearing their eyes only. They are rejected from marriage and rejected.”

With stigma the poverty, and difficulty. Then diseases that have no obvious cause: skin diseases, heart conditions, kidney failure, cancer. Symptoms everywhere – but no one can explain to them.

Over time, focus is transferred to second and third generations.

BBC / Hyojung Kim

BBC / Hyojung KimHan Jeong-Sun, a Surfivor of Second Generation, suffered from avascular necrosis in his waist, and could not walk without dragging himself. Her first son was born with cerebral palsy.

“My son never walked a step in his life,” he said. “And my servants who treated me. They said, ‘You have borne a lame child and you are broken again – you are also in harmony with our family?’

“That time perfect hell.”

For decades, even Korean government with active self-interest victims, as a war with the north and economic struggle is treated with higher priorities.

Up to 2019 – Over 70 years after bombing – Mohw released the first report of finding the truth. That survey is mostly based on questions.

In response to the BBC’s questions, the ministry explained that before 2019, “no legal grounds of funding or official evaluation”.

But two separate studies know that second generation victims are more susceptible. One, from 2005, showing that the second generation victims were more than the majority of the population suffering from depression, heart disease found their disability registration is almost double the national average.

Against this backdrop, Ms Han is unbelievable that the authorities continue to seek proof of knowing him and his son as a victim of Hiroshima.

“My illness is proof. My son’s disability is proof. This pain passes generations, and it appears,” he said. “But they can’t recognize it. So what do we need to do – just die unknown?”

Peace without apology

Last month, on July 12, Hiroshima officials visited Hapcheon for the first time to put flowers in a memorial. While former PM Hatoyama Yukio and other private numbers come before, this is the first official visit to the current Japanese officials.

“Today in 2025 Japan talks about peace. But peace without forgiveness is worthless,” says Junko Ichiba, a long life life suggested by the victims of Korea Hiroshima.

He pointed out the officials to visit without talking about or apologize to Japan’s treats before and during the world war.

BBC / Hyojung Kim

BBC / Hyojung KimAlthough many former Japanese leaders offer their forgiveness and depression, many South Korean people have considered these feelings of poorly informal recognition.

MS Ichiba says Japanese books are still not in Korean colonial history – as well as atomic bombs – saying “This unreasonable”.

It adds what plenty of views as a wider lack of accountability for Japan colonial heritage.

Heo Jeong-gu, Director of Red Cross Support

For those who survive like Mr Shim it’s not just about the charge – it’s about identification.

“Memory is important than a fee,” he said. “Our bodies remember what we’ve been through … If we forget, it will happen again. And for some day, no one left to tell the story.”