At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. government approved a record-breaking spending bill totaling $5 trillion to keep businesses afloat, jobs and the economy from falling into recession. Five years on, somehow the U.S. economy has not only avoided contraction but has managed to grow—an outcome many investors thought was impossible.

By 2025, the White House announced another major stimulus package, President Trump’s A Big and Beautiful Act. Projections from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) put the bill’s cost, the additional burden on the national debt, at about $3.4 trillion.

While most economists agree that the revenue generated by tariffs will offset much of the spending, the fact remains that a large amount of stimulus is being pumped into the economy at a time when it is not only already stabilizing but also growing.

The Federal Reserve is expected to take further stimulus measures in the form of interest rate cuts. While inflation remains around 3% (above the Fed’s 2% target), voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee have indicated they are open to multiple rate cuts, with Trump appointee Stephen Miran even advocating for a 50 basis point cut by the end of the year.

That raises the question: Why, between the central bank and the White House, is Washington acting like the U.S. is in recession — or at least preparing for one.

The Fed could cut interest rates for a number of reasons: The central bank may indeed feel that its monetary policy of 100 basis points above inflation is too restrictive. Or, its board members could vie for Trump’s attention to replace Chairman Powell next year. Or maybe it sees weakness in economic data and is trying to look beyond that.

Ken Griffin, CEO of Citadel This question has been raised. Speaking at a conference in New York earlier this month, Griffin said Trump 2.0 policies had created a “sugar high” in the market due to its pro-growth agenda. Even so, he warned that further stimulus might be better suited to a recession rather than “a period of near full employment a few years into the business cycle.”

Does Washington know something we don’t?

If the U.S. falls into recession, policies in Washington (from the central bank or the White House) may make more sense. Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi said this is actually the case in more than half of U.S. states In a recent note, Zandi found that the economies of 23 states in the United States are shrinking, only 16 states are growing, and 12 states are classified as “stagnant.”

Zandi has said before wealth Many people’s consumer sentiment is consistent with the recession, except for the fact that they currently have jobs: “People’s view of their economy, their financial situation is very consistent with the recession — the difference is they didn’t lose their jobs. Having said that, our unemployment rate is 4.3%… Even in a recession, our unemployment rate was only 5% or 5.5%, so we’re talking about a percentage point… That’s not a lot of people. You might say that’s not a great outcome.” A litmus test for whether you’re in a recession. ”

But Zandi told wealth In an exclusive interview, the White House certainly isn’t charting a course based on such concerns: He believes the goal of OBBA is to create enough positivity to propel the administration through next year’s midterm elections.

The Fed, however, is a different story: “The Fed is more focused on growth and employment. They see the job market moving sideways… Unemployment is low, but unemployment is rising, especially among young people, which I think is most important. They are keeping inflation risks down because inflation expectations remain stable and (the Fed) believes that the rise in inflation from tariffs will be more of a one-off and less persistent.”

Zandi added that the Fed is “rightly right” to have concerns about its independence. “I think they’re desperate to avoid a recession because if one does happen, they’ll be blamed and their independence will be more seriously threatened as a result. So I think they’d be better off making the mistake of supporting growth, not to mention worrying about future inflation.”

On the other hand, Macquarie chief economist David Doyle said wealth While Washington won’t necessarily shape policies because of concerns about a looming recession, policymakers will be keen to sustain growth. He warned that it was a fine balance that needed to be maintained, which could overstimulate the economy: “If they succeed — and the Fed and the government succeed together and avoid a recession — by 2026, maybe the risk will be the other way around: Is there going to be an overheating?”

Doyle added that there’s a good chance people will start talking about the Fed raising interest rates next year. “Inflation looks to have been declining steadily and now appears to be stalling at around 3%. If we do see the labor market pick up and potentially pass on more tariff prices… then inflation will be higher in 2026.”

Are current policies appropriate?

While Washington’s policies may avert disaster in the short term, the question remains whether it is appropriate to approve such a massive stimulus during a relatively stable period in the economic cycle, especially given recent administrations Government shutdown (which happened because of the debate in Congress over spending)).

The 2025 shutdown is happening because Democrats want to see an extension of tax credits and continued spending for health agencies, both of which come directly from federal funds. Although Republicans oppose the spending, they have been willing to extend and approve tax cuts that would reduce federal revenue to $4.5 trillion, according to calculations by the Bipartisan Policy Center.

In theory, governments should run larger deficits during periods of higher unemployment: they spend more money to stimulate the economy while receiving less tax revenue from employed workers. Budgets should be more balanced when the economy is doing well, the need for government stimulus is reduced, and opportunities for increased tax revenue are greater.

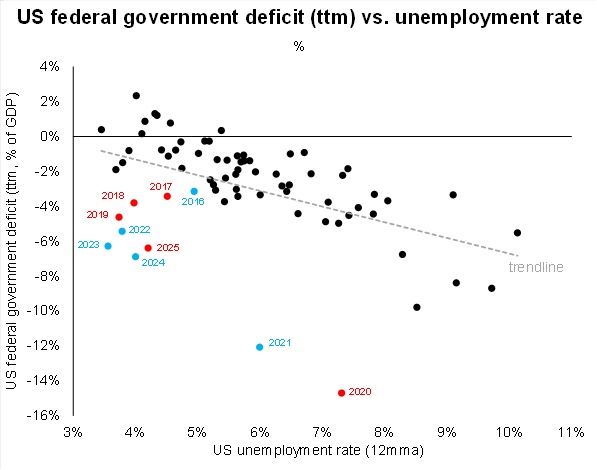

Macquarie’s research found that with the national debt now approaching $38 trillion, governments – regardless of party – have increased deficits since 2018 at levels higher than the historical average under similar economic conditions. Macquarie plotted the U.S. unemployment rate against the federal deficit as a percentage of GDP and found that historically an unemployment rate of about 5% would result in a -1% change in the deficit. The correlation before 2018 declined steadily as unemployment rose, with an unemployment rate of 8% resulting in a deficit change of -4%.

This correlation changed in 2018, indicating that macroeconomic conditions and the federal budget have become increasingly disconnected. For example, a relatively stable 4% unemployment rate in 2019 still resulted in a deficit change of -4%, while a similar unemployment level in 2024 resulted in a further deficit decline of -6%.

“The key takeaway I tell our clients is: Typically, when unemployment hits 4%, the deficit would be -1% or even (can you believe it?) a balanced budget. Now we’re in a regime of like -6, -7%, that’s a broader structural deficit. That’s a problem, which means if we do go into a recession and job losses, assuming unemployment spikes to 7% or higher, you’re probably talking about a deficit of -12%,” Doyle added.

“In this scenario, how will the United States fund its long-term debt and how will it fund its deficit?” Doyle asked.

This is not the moment when investors begin to question the viability of debt Simply put, it is the scale of debt (After all, government borrowing provides the basis for the bond markets that are one of the backbones of the global economy.) But whether a country has the ability to repay or repay its debt, or whether it will resort to quantitative easing to balance the books and dilute the value of investments. That’s why economists are so concerned about a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which is basically whether a country is growing enough to justify its borrowing, which is expected to soar to 156% by 2055 According to the Congressional Budget Office.

Zandi believes that this path is justified if the current fiscal plan not only covers costs but also promotes economic growth. He added: “You’re going to get some stimulus with this beautiful big bill: it’s already stimulating and it’s adding some stimulus, so from that perspective it’s not unprecedented.”

Stimulus or not, the U.S. economy still has a mountain to climb before Washington’s debt is more aligned with its economic environment. Zandi added: “The level of support for the economy since the pandemic has been unprecedented. When there is full employment, the primary deficit should be zero and there should be a surplus.”

Zandi noted that even a “relatively modest and small” stimulus could exacerbate debt concerns. “We’ve got huge deficits and huge debt and we’ve done nothing about it – quite the opposite. So in that sense, it’s unprecedented.”