Getty images

Getty imagesIt was late at night after 10 December 1987 if the prison officers were crying Mzolisi Dyasi in his cell in South Africa’s eastern door.

He remembers the flowing drive in a hospital hospital that he was asked to distinguish the bodies of his pregnant girlfriend, his cousin and a co-anti-apartheid fighter.

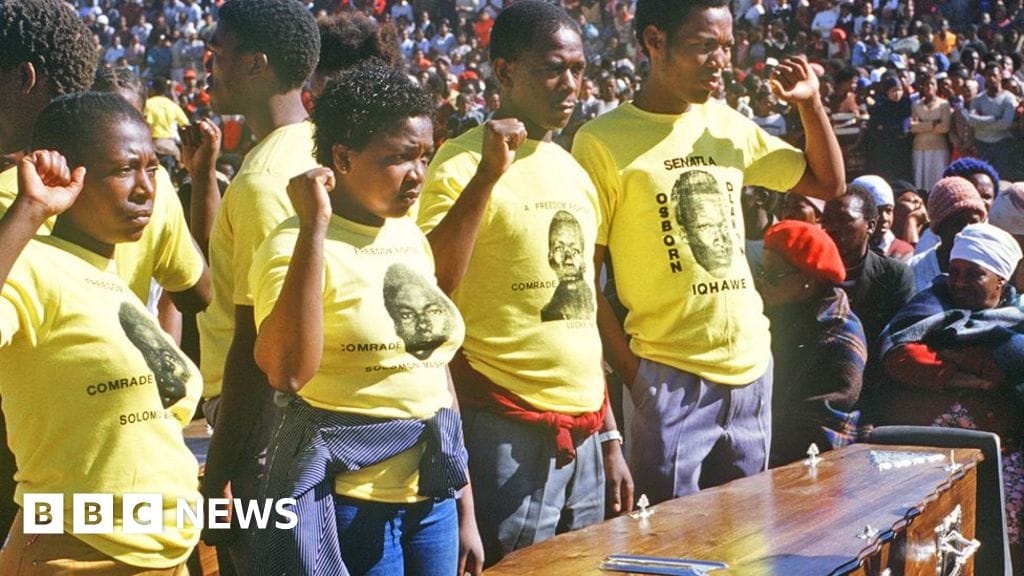

In response, he fell on a knee, raised his fist in the air, and tried to scream “Amandla!” (“Power” of Zulu), in an act of opposition.

But the word got his throat as he “completely broken”, Mr. Dyasi told the BBC, remembering the sight of his loved ones under cold, bright lights.

Four decades were asleep at the lights of the lights to prevent memories of the physical and mental torture he suffered in his four-year imprisonment.

He said he was struggling to build a life for himself in society that he faced as an underground operation that had been with the Acrican National Congress (ANC).

The Anc led the struggle against the racist apartheid system, which ended in 1994 with the party’s rise in the first African choice.

A commission of the truth and reconciliation (TRC), internationally led Cleric Archbishop Desert Tutu, and a reparation of the victims was set to help some of the victims.

But most of that money never causes.

Mr. Dyasi is one of the 17,000 people who have received an off payment of 30,000 rand ($ 3,900; £ 2,400 in time) from it in 2003, but he said little to help him.

He wants to complete university education but has not yet been paid for the courses he took in 1997.

Now at the age of 60, he suffered from health issues and found it difficult to obtain medicine in the special pension he received in the struggle for freedom and democracy.

Mzolisi Dyasi

Mzolisi DyasiProfessor Tshepo Madlingozi – a member of the Human Acrica Commission Commission communicating with the BBC in his personal capacity – says the effects of apartheid continue to harm.

“Not just about killing people, people lose, about locking people in disability.”

He said that despite the progress made during the past 30 years, many of the “born generations” – was inherited in South Africa after 1994 – inherited the cycle.

The fund reparations have about $ 110m unspecified, with no explanation of why this is the case.

“What’s money used? Is there any money?” Prof Madlingozi commented.

Government does not respond to a BBC request for comment.

The lawyer Varney Varney spent most of his career that represents the victims of apartheid-era crimes and says that the South African story is affected “for families affected.

Now he represents a group of families and survivors of victims that hurt the South Africa government for what they say is highlighted by political crimes for further investigation and prosecution.

Brian Mphatleele is polite and said softly; Stop him before responding to a question, as waiting for his thoughts in his mind.

He suffered from memory loss, only one part of the lasting effect of the physical and psychological torture he had passed through the famous Cape Town prisoner.

Mr Muthelele told the BBC that the 30,000 rand pay-out, which he received for the violations he suffered in his 10 years in prison, an insult.

“It went through my fingers. It went through everybody’s fingers, it was so little,” The 68-year-old said on the phone last year from his Nephew’s home in Lang Township in Cape Town, where he lived.

He felt that the greater payments could buy him his own house and described his failure in his life in Langa, where he ate a kitchen soup three times a week.

Since he was talking to the BBC, Mr Mphahlele died, his hope of a more comfortable life was not fulfilled.

Prof Madlingozi says South Africa has become a “poster child” reconciliation after the end of apartheid, and encouraged the world in many ways.

“But we also accidentally given a wrong message, which is that a crime against mankind can be committed without a result,” he said.

Even if he feels things to be more.

“South Africa has an opportunity of 30 years of democracy to indicate that you can make mistakes and heal errors.”

Mr. Dyasi still remembers the feeling of freedom and optimism when he left Jail in 1990 Nelson Mandela to be the first black president four years ago.

But Mr. Dyasi said he could not be proud of who he was today, and his disappointment felt a lot besiege him and their families.

“We don’t want to be a millionaire,” he said. “But if the government can only look at health care of these people, if it can see their living, it will participate in the country’s economic system.”

“There are kids who are restored to the struggle. Some children want to go to school but they still can’t do. Some people are homeless.

“And some people say, ‘You have been prisoner, shot you. But what do you show it?'”

Getty Images / BBC

Getty Images / BBC