Joe Tidy,BBC cybersecurity correspondentand

Farshad Bayan,BBC Persian

NurPhoto via Getty Images

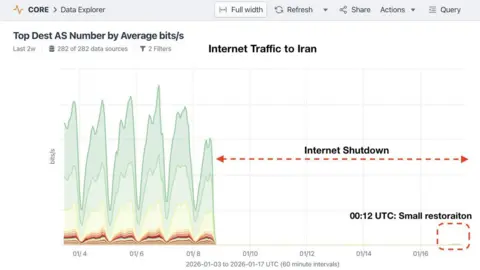

NurPhoto via Getty ImagesIran is 10 days into one of the worst internet shutdowns in history, with 92 million citizens cut off from all internet services and even phone and text messaging disruptions.

The Iranian government cut services on 8 January, apparently to suppress dissent and prevent international scrutiny of a government crackdown on protesters.

Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said the internet was cut in response to what he described as “terrorist operations” ordered from abroad.

The government has not said when internet services will return, but new reports suggest that, behind the scenes, authorities may be making plans to restrict them permanently.

On January 15, the news website IranWire reported that government spokeswoman Fatemeh Mohajerani told reporters that international web access would not be available until at least the Iranian New Year in late March.

Internet freedom watchers at FilterWatch believe the government is rushing to implement new systems and rules to cut off Iran from the international internet.

“There is no expectation of reopening international internet access, and even then, access to international internet users will not return to its previous form,” FilterWatch said, citing unnamed government sources.

While the BBC could not independently verify this report or the timing of its implementation, journalists who spoke to BBC Persian also said they were told that internet access would not be restored anytime soon.

From temporary loss to “communication black hole”

Iran has maintained a tight grip on the internet for years, with most western social media apps and platforms blocked, as well as outside news websites such as BBC News.

However, many people are able to access popular apps like Instagram using Virtual Private Networks (VPNs).

Internet freedom campaigners at Access Now say Iran often uses shutdowns as a way to disguise mass violence and brutal crackdowns on protesters, as seen in nationwide internet shutdowns during the November 2019 and September 2022 protests.

reflection

reflectionA shutdown was also imposed during the Iran-Israel conflict in June 2025.

However, the current blackout lasted longer than any previous shutdown.

In a public statement, the charity Access Now said that the full restoration of internet access is essential.

“Restricting access to these essential services not only endangers lives but encourages authorities to cover up and avoid accountability for human rights abuses,” it said.

There are reports that livelihoods in Iran have been severely affected by the shutdown of e-commerce.

As of January 18, the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) estimated that more than 3,300 confirmed deaths of protesters had been recorded, with more than 4,380 cases being investigated. It also reported that the number of arrests has reached 24,266 in 187 cities.

The actual number of people killed and detained is believed to be much higher, but a lack of access means the numbers cannot be independently verified.

The Internet monitoring project, FilterWatch, said the latest shutdown heralded the start of a more severe “digital isolation” and increased surveillance of what is said, sent and viewed online.

Amir Rashidi, director of cyber security and digital rights at the Miaan Group, which runs FilterWatch, told the BBC that he believes the authorities are moving towards a tiered system where access to the global internet is no longer automatic but subject to consent.

Access will be granted through a registration and vetting process, he expected, adding that the technical infrastructure for such a system has been in place for years.

Who decides about the Internet?

According to FilterWatch, the plans are not discussed publicly, with important decisions being concentrated more within the security bodies than the civilian ministries.

Protecting Iran from cyber attacks — of which there have been several high-profile and disruptive cases in recent years — may be another motivation for extreme moves.

However, analysts warn that the plans may not be fully realized or may be applied unevenly due to internal power dynamics and broader economic and technical pressures.

Amir Rashidi says that the risks of internet providers, along with the ability of users to adapt or migrate to alternative platforms, may further complicate the implementation.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty ImagesIf Iran goes ahead with the reported plans, it will follow the same systems as Russia and China.

China leads the world in internet control not only with massive state censorship of online discussion but also what people outside of the country can access.

The so-called Great Chinese Firewall blocks citizens from most of the global internet and all western apps like Facebook, Instagram and YouTube are inaccessible without VPNs – but they are also becoming more difficult to use.

In 2019, Russia began testing for a large-scale plan to create a similar system called Ru-net.

But unlike China, which built state control over the internet as the web spread decades ago, Russia has had to retrofit state control over complex systems.

Russia has gone one step further than China and is planning to withdraw itself from the global web using a “kill switch”, which will apparently be used in times of crisis.

The system allows internal internet traffic and will keep the country functioning online but no outgoing or incoming traffic – a digital border in effect. But it has not been fully tested.

Where is the internet in Iran going?

If reports are accurate, Iran seems to be planning a quasi-combination of permanent internet control with China and Russia.

“In Iran there seems to be a move to isolate everyone from any electronic access, unless approved by the government,” said computer security expert Prof Alan Woodward from Surrey University in the UK, after reviewing reports of Iran’s plans.

He believes that the Iranian regime is probably pursuing longer-term plans, using the current blackout as a reason to make technical switches and orders now, while everything else is being cut.

Amir Rashidi says the question is no longer technical, but political – arguing that whether such systems are fully implemented now depends on political will.

Mobina / Getty Images

Mobina / Getty ImagesStarlink and other internet-from-space services, known as Low Earth Orbit (LEO), have also been complexly controlled by Iran during the protests.

LEO’s internet services allow users to bypass all censorship and closures by connecting through satellites.

The government managed to jam and interfere with some Starlink users but it was confirmed by the BBC that other terminals remained operational after the company updated its firmware to evade the government’s control efforts.

The service, owned by Elon Musk, the subscription fee is also waived for Iranian users.

Despite the increasing number of tools used by repressive regimes, Woodward is surprisingly optimistic about the future of the internet.

He cited the advances in LEO and the fact that many phones can now use satellites even when the internet is down for things like SOS messages.

There are also emerging apps that use mesh networks that rely on Bluetooth, which can bring connectivity when there isn’t one.

“It is almost inevitable that internet access will become truly universal eventually but it will always be cat and mouse for repressive regimes”, said Woodward.